The thundering forward march of technology inevitably shakes loose latent fears in society. Examples range from rightful concern of economic displacement – as with the Luddites opposing automation of textile work – to scaremongering over what is new, seen with the 19th century fears of evil spirits emanating from telephones.

Even before today’s AI frenzy, there was a chorus of voices warning that AI-enabled automation would create structural unemployment that destabilized the US and other economies. Andrew Yang managed to raise more than $40M and get 5% of the vote for President in the Iowa caucus by focusing his 2020 campaign primarily on this issue.

Andrew Yang Speaking at an Event in San Francisco

Others are dismissive of the labor effects of AI and are quick to say AI is just a tool. The reality is more nuanced. Not all AI is created equal; its applications are not a single monolith, which will become clear as we get further down the adoption curve. We need to discuss AI-based automation within a continuum framework which it will likely inhabit in practice as implementation expands.

At the top of the continuum are productivity tools that complement workers and complete only a portion of a job or task. In some situations, higher productivity per worker can result in fewer workers if demand is capped. In aggregate, however, improving output per worker lowers costs, leading to a new equilibrium price and more potential customers.

For example, electronic design automation (EDA) companies like Cadence and Synopsys have been introducing AI solutions to their chip design tools to reduce design costs, improve yields and shorten time to market. Today, chip design is constrained by the number and distribution of capable engineers, with a host of companies and nations that would gladly backfill demand if design prices decreased. Rather than reduce the demand for design engineers, AI creates more aggregate activity through improved productivity.

Next is “Enabling Automation”. Here AI completely replaces a job or task, but that job was not an end in and of itself. Rather it was a prerequisite to enable another critical business need.

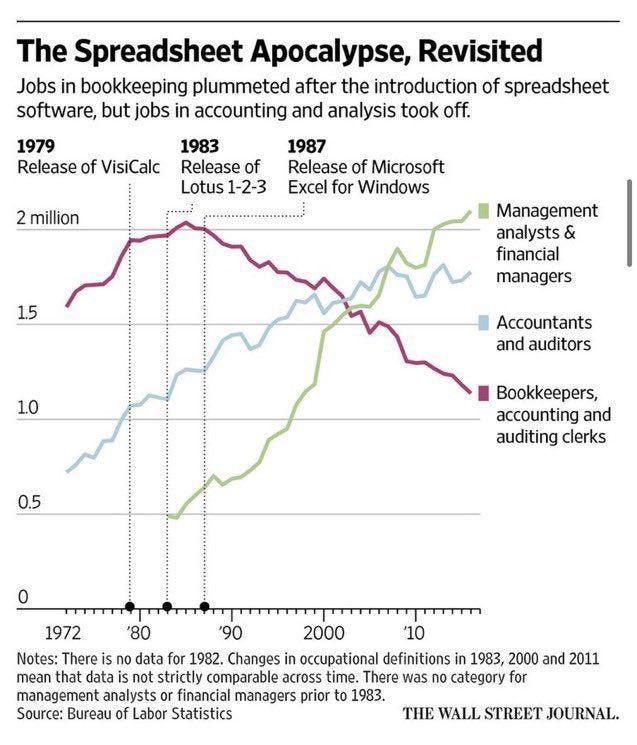

The best example is bookkeeping and financial analysis. Bookkeeping has a functional purpose: companies need to know that all the accounts are correct and money is not lost. Bookkeeping also serves a financial data preparatory purpose. Unless I know how much the Accounts Receivable balance was in each month, I can’t look at how it has trended over time and determine whether and why customers are paying me slower.

Companies used to have teams of bookkeepers that kept ledgers and tallied financial statements by hand. When spreadsheet software was introduced in the 80’s, much of the bookkeeping work that was previously done by hand could now be done by software and bookkeeping jobs declined precipitously. Yet, by enabling the financial data preparation, bookkeeping jobs were more than replaced by financial analyst roles that could deliver insights of greater value to the business.

The final leg of the continuum is “Replacement Automation”. This is when the task automated is the end. When one hires a trucker to get goods from point A to point B, autonomous trucking could, when ready, replace the human driver. These jobs are fully displaced.

However, not all job displacement is a bad thing. Some jobs are unpleasant. Washing machines replaced a lot of back-breaking labor that was spent on hand washing clothes, creating opportunities to spend the time elsewhere.

It is possible for a technology to move down the continuum as it progresses. Someday, AI may be able to do all the jobs of a financial analyst, and a program will simply serve insights directly to the CEO without the need for any analysts, let alone bookkeepers.

To fully understand the impact of AI on jobs, we need to consider not just this job displacement spectrum, but also the new industries that may be created through the AI wave. When the iPhone came out, it would have been difficult to envision how that would enable the gig economy and the myriad jobs created driving for Uber, managing Airbnbs, or doing handywork as a taskrabbit. (Whatever some may think about whether those are desirable jobs, there are many glad for the opportunities.) There will likely be future swaths of the economy that would not have been possible before the advances in AI and employ many, many people. We shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the number of jobs in the economy is not constant.

It may be catchy to declare definitively that AI will destroy either all or zero future jobs. But I believe the more useful approach is to try to analyze our inevitable AI evolution within the context of this continuum of automation and also consider on balance the new industries that will likely be created through AI. Certainly before taking any drastic actions like Universal Basic Income.

As Rob Atkinson recently pointed out on the TechSurge podcast, historically when technology removes jobs, people have more money to spend on other things, in turn creating jobs in other areas of the economy.

The potential concern with AI is that as a digital technology it can proliferate quickly, causing rapid change in the economy and displacing workers faster than the equilibrium can adjust for. Or, in a more extreme scenario, some AGI or super intelligence is achieved that can do the job of any human.

Rather than worrying about a future state about which even the “godmother of AI” doesn’t feel comfortable making predictions, it’s better to take a wholistic view and address concerns and policy solutions for the incremental reality we have come to expect.