Lessons from History: The Power of Design & Manufacturing Synergy

One of the great privileges of the modern era is our access to historical knowledge. Anyone with a library card or internet access can find long form accounts of the great achievements of history, often directly from participants.

Despite this ready access, we don’t always take advantage of it. This is certainly true in the world of technology startups. There is value in being unburdened by the mistakes of the past when approaching an audacious goal, but it should also be bolstered by learning from the successes.

As much as venture capitalists prefer to think each company’s success is an individual achievement, startups exist within broader technological trends and often borrow ideas and practices from their predecessor companies. Studying Sears can help understand Amazon, just as the rise of online brokerages like E-Trade can tell us a lot about what we may expect from Robinhood.

As an investor in deep tech startups, I have a particular affinity for accounts of teams that created products in industries where tight manufacturing tolerances made others believe an upstart group could never compete with established players. Lessons in this area are especially pertinent today as re-shoring manufacturing to the US has become a stated policy goal.

Post-World War II, the Big Three U.S. automotive companies – GM, Ford, and Chrysler – were completely dominant domestically. At their peak, they made up 20% of the US Gross National Product. In contrast, Japan, ravaged by war, was struggling with pervasive hunger and scarce housing while trying to build the beginnings of an industrial base. Yet, only a few short decades later by the early 1980’s, Japanese auto companies had surged to >20% of the US market.

There are myriad reasons the Japanese were initially able to capture share including disparity in labor costs, the 1979 Oil Shock tilting demand to smaller, more efficient cars, and a weak yen. But the biggest reason the Japanese held on to that market share was because of their commitment to quality in manufacturing. Central to this commitment were the teachings and system of W Edwards Deming. David Halberstam writes in The Reckoning that Deming’s system was based on a simple premise:

Engineers should not be separated from the manufacturing line in some nice sanitary office, but should be out on the factory floor as much as possible, as much a part of the line as the workers themselves.

One of the great Aerospace accomplishments of the last century is the F-117 Nighthawk, originally a proof of concept called Have Blue designed by the Lockheed Martin Skunkworks division. The Nighthawk was the first aircraft to incorporate stealth technology, a unique, carefully designed shape that reduced radar cross-section.

However, many, including former Skunkworks leader Kelly Johnson, were skeptical the plane would even fly because of its odd shape. Not only did it fly, but Skunkworks delivered the first five aircraft in only 5 years and for only $350M. In his memoir on leading Skunkworks, Ben Rich opines on how Skunkworks accomplished this feat of execution:

We had our own unique method for building an airplane. Our organizational chart consisted of an engineering branch, a manufacturing branch, an inspection and quality assurance branch, and a flight-testing branch. Engineering designed and developed the Have Blue aircraft and turned it over to the shop to build. Our engineers were expected on the shop floor the moment their blueprints were approved. Designers lived with their designs through fabrication, assembly, and testing. Engineers couldn’t just throw their drawings at the shop people on a take-it-or-leave-it basis and walk away.

Prior to Tesla, the history of automotive startups in the 20th century is more of a post-mortem. Even the combination of successful airplane manufacturer Henry Kaiser and Detroit insider Joe Frazer in the 1940’s automotive boom couldn’t compete with the Big Three.

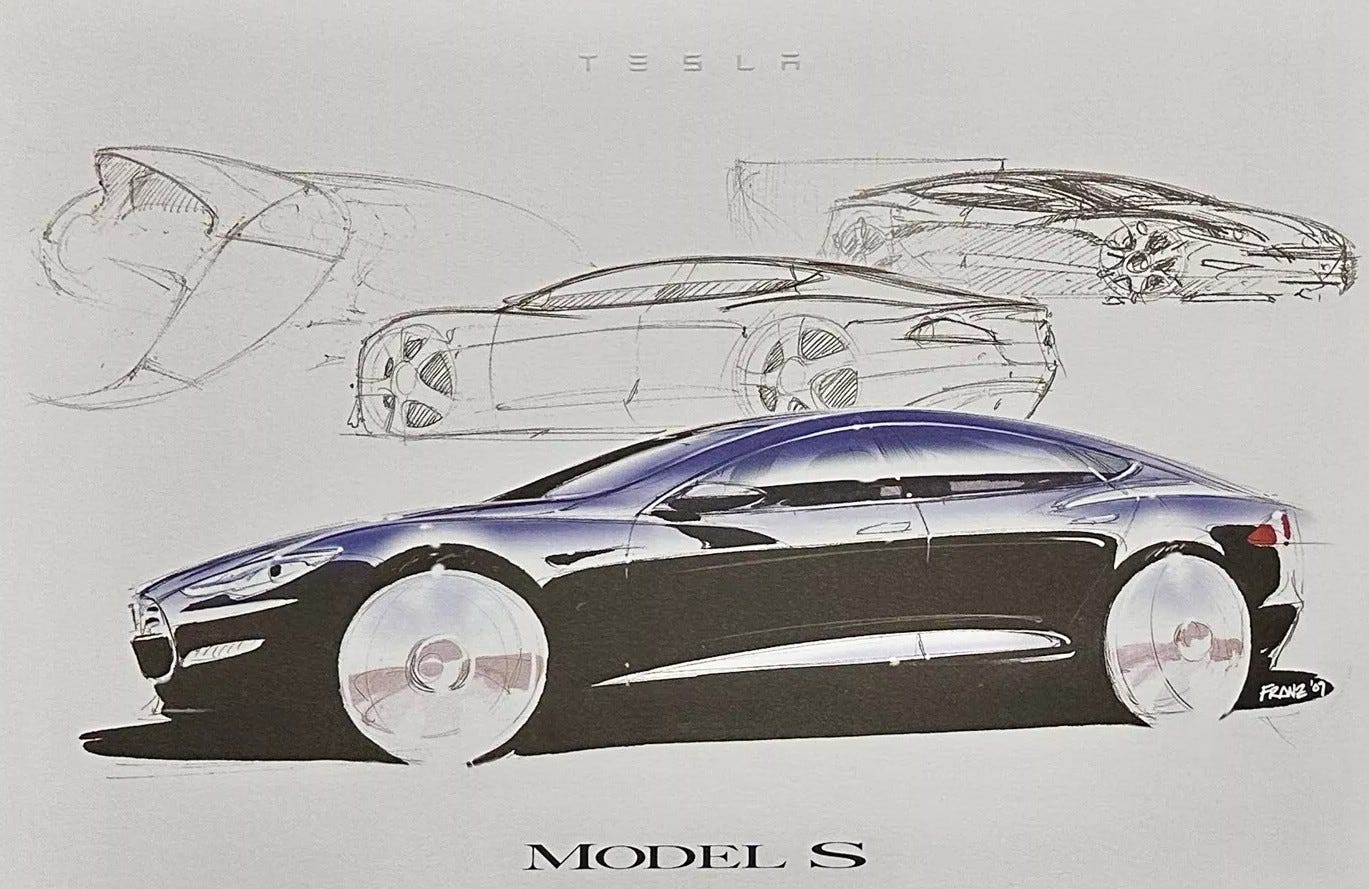

It was broadly assumed that the combination of the wage scale of US workers and the required capital investment in manufacturing made it impossible to launch a profitable US auto company. The launch and production scaling of the Tesla Model S in the 2010’s disproved these doubts and made possible the Tesla of today. Walter Isaacson writes of the Model S in his Elon Musk biography:

It was an example of Musk’s policy that the designers sketching the shape of the car should work hand in glove with the engineers who were determining how the car would be built. “At other places I worked,” [Lead Designer Franz] von Holzhausen says, “there was this throw-it-over-the-fence mentality, where a designer would have an idea and then send it to an engineer, who sat in a different building or in a different country.” Musk put the engineers and designers in the same room. “The vision was that we would create designers who thought like engineers and engineers who thought like designers”

A "throw it over the fence” mentality between design and engineering pervades most organizations. These groups, though common knowledge said their goal was nearly impossible, chose to eschew the norms. Across different decades, continents, and industries exceptional manufacturing achievements consistently involve tightly integrated design and engineering teams throughout the process.

For those aspiring to drive the next wave of manufacturing innovation, history offers a clear lesson: cultivate small, highly motivated teams where design and engineering disciplines are intertwined, ideally co-located, fostering continuous collaboration.